3 transformative ideas to put people back into the centre of politics.

About five months ago I realised my heart was playing up again.

It’s happened before.

A few years ago I had a heart attack.

Back then, I was on the waiting list for a scan.

The scan hadn’t happened because I’d left it too late. I ignored the warning signs, flew all over the world, and only, finally, visited my doctor ‘when I had time’.

He put me on a waiting list.

My heart didn’t wait.

I had a heart attack.

My fault.

Operation.

Convalescence.

I resumed my life.

Now, noticing signs my heart was struggling again — tiredness; slight shortness of breath; tension in the chest — I took responsibility.

I visited my doctor (a new doctor in a new country). She put me on the waiting list for a scan — sufficiently concerned to designate me ‘urgent’, though I’m functioning well and feel healthy.

That was five months ago.

I’m waiting.

Five months as an ‘urgent’ patient, in danger of a potentially catastrophic, entirely preventable, health crisis.

I might get seen in late January.

Perhaps.

That’ll be for a scan. Then, I guess, there’ll be another waiting list for treatment.

I’m in a race between an under-funded health system and my under-performing heart.

A couple of months ago, I received a letter from the health service. It asked if I still needed the scan.

What does that mean?

In what circumstances would I NOT, any longer, need an urgent scan to diagnose a potentially fatal condition?

I can think of only two.

Either I’m rich enough to have been sought treatment outside the public health system.

Or, I’ve died.

It hit me hard.

They want to know if I’m rich, or (conveniently for the statistics perhaps) dead.

I’m neither.

So I wait.

Perhaps I’ll die waiting.

On the level of ‘policy’, this much is clear: I’m not rich, so I don’t matter very much.

It doesn’t matter if people like me live or die.

If that sounds overdramatic, I’ll rephrase it.

The life of people who aren’t rich is a lower priority than other policy objectives — chief among them, keeping taxes low for the wealthy, well-connected, and for corporations.

Underfunding the health system results in long waiting lists. It’s inevitable. It’s a policy choice.

Put crudely that policy choice is: ‘how many not-rich people should we allow to die?’

It’s not only in the realm of health that the needs of the majority, the not-rich, come low on the list of governmental priorities. In education, transport, social housing, access to natural environments, ability to keep warm, availability of stimulating and diverse culture, healthy and nutritious food, genuine democratic representation — in fact, every aspect of the fabric of a decent, human life — if you’re not rich, you don’t much matter.

This isn’t an abstract discussion.

Not to me.

Not right now.

It’s about my survival.

I’m not poor.

I’m not struggling, destitute, or part of a marginalized underclass.

I survived well enough. I have a home and can (just about) afford to heat it.

There’s food on my table.

I’m more comfortable than many of my fellow citizens. I’m utterly grateful — especially these days, as we watch unfettered viciousness meted out to the neediest and defenseless at home and abroad.

I live in a country less vicious and more compassionate than most.

I’m not poor — not by the definitions we used to have.

But ‘poor’ needs a new definition.

‘Poor’ these days means ‘not rich’.

Economists and sociologists write of the ‘hollowing out of the middle classes’. It’s happened across the Western world, but is nothing new,

The erasure of the middle class is a cyclical reversion to the norm.

There are only two classes — Rulers and Ruled.

The middle class is a useful fiction, a convenient buffer between rulers and ruled. The middle classes — in which I include myself — are useful idiots. We’re trained to aspire upwards and kick downwards.

The thing is, we’re not rulers, we’re the ruled. We’re kept in place by an implacable elite comprising the hereditarily connected, corporations, and the rich.

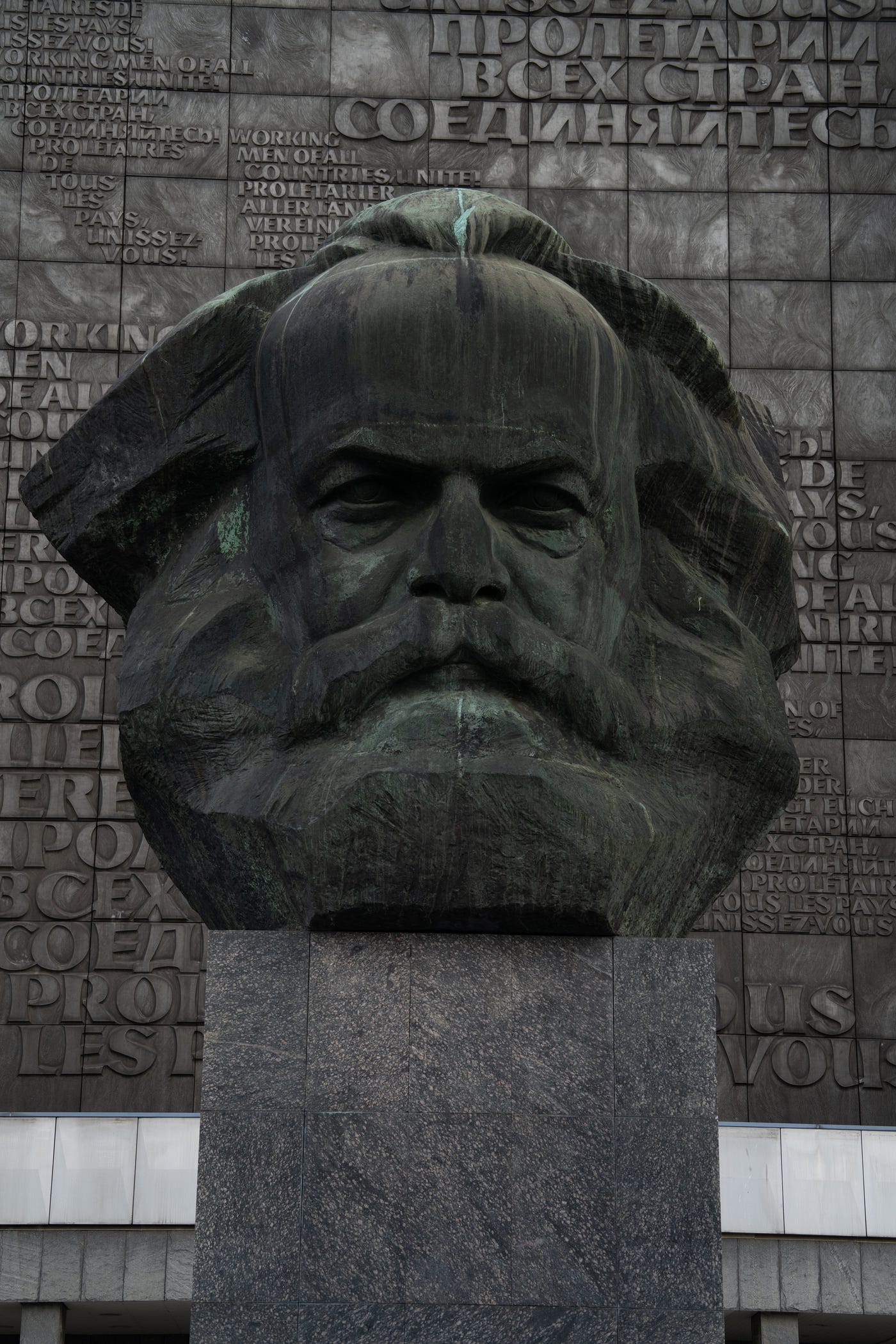

All very Marxist.

All very theoretical.

Except this isn’t theoretical.

My heart is failing and I’m scared.

There’s nothing I can do.

I understand, with a visceral force, that I don’t matter.

I’ve tried to contribute what I can, to be kind, to live with compassion.

I’ve succeeded sometimes.

I’ve failed sometimes.

It doesn’t matter.

I don’t matter.

I’m not rich.

The systems we live in, and the policies we live by, are chosen. They’re not immutable ‘laws of the universe’.

The people who rule make conscious, deliberate choices that some things, some people, matter more than others.

That’s inevitable.

Choices have to be made.

Policies must be implemented.

Priorities, though, can change.

Different choices can always be made.

Those who make and implement policy are mostly either of the establishment class or are effectively owned by them.

By ‘owned’ I mean they’re given money in return for service: ‘we fund you, or use our media to support you. In return you implement policies that advantage us’.

‘Owned politicians’ are advocates for, and obedient servants of, the privilege of the people who fund and support them.

They gain the support of the powerful by promising, loudly, repeatedly, and fawningly, not, in any substantive way, to challenge the power of the elites. They create an illusion of progressive possibility, and so conceal the brutality of the system they maintain.

Sometimes the people at the top are not merely servants of the elite, they’re visibly part of the ruling class — wealthy oligarchs like Trump or Sunak; hereditary insiders like Johnson, Bush, Biden, or Rees-Mogg; leaders of ‘establishment’ parties like Fine Gail or Fainna Fáil in my home country, Ireland.

When a genuine challenge comes? Jeremy Corbyn? Bernie Sanders? Progressive left parties? Leftist leaders in South America? Environmental radicals?

The establishment first ridicules then demonises, and destroys them. The power structures insist we believe progress and change are impossible. They entrench Thatcher’s rallying cry of ‘There Is No Alternative!’.

Potentially progressive politicians and thinkers are blocked from access to power, or (in the case of many activists) imprisoned or killed.

Should radicals actually achieve power, they face violent removal. As the oligarch Musk boasted after a US-backed coup against a progressive government in Bolivia:

‘We will coup whoever we want!’

His ‘we’ is an explicit acknowledgment of the intimate interconnection of oligarchs and the governments they own.

The ideological justification the ruling class used to explain their power evolved: Feudalism, the Divine Right of Kings, White Supremacy, Colonialism, and Manifest Destiny.

Yanis Varoufakis’ latest book claims Market Capitalism is now dead, superseded by a new mechanism by which the few will dominate the many: ‘Technofeudalism’.

New names, same old meanings.

One ‘class’ of person rules over the rest.

The dominant global justification in our era has been Neo-Liberalism, or, as I prefer to call it, Capitalist Extremism.

We’re told it’s the only viable system.

We’re told there’s no alternative.

We’re asked to accept that, in a world that’s abundant, and in which there could be enough for all of us to eat and live well, we must struggle, compete, fight, and defend ourselves against one another — because that’s how the system is.

It’s a lie.

It’s a story the ruling class tells to explain why they are and intend to remain, in charge.

Contemporary neo-liberalism emerged from the work of Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek. Hayek was funded by mid-twentieth century oligarchs (especially Harold Luhnow — head of the William Volcker Charitable Fund) via the Mont Pelerin Society.

Hayek’s free-market fundamentalism was given intellectual respectability, by The Chicago School of Economics and the (oligarch-endowed) Chair of Economics held by Milton Friedman.

Thatcher and Reagan were converted and injected the toxicity of neo-liberal ideology, evolved by the powerful to serve the powerful, into the bloodstream of Western, then global, politics.

Their mini-me bastard offspring have continued to implement Capitalist Extremism, funded by the establishment and their wholly-owned media outlets.

We’re constantly told it’s the only viable ideology.

In truth, it’s simply another manifestation of the ancient ideology of privilege.

Hayek believed a key role of government was essentially to protect the wealthy from the demands of the masses.

He saw freedom of the markets as fundamental freedom.

Democracy, he believed, was optional.

By definition, those who could have the greatest impact on the markets — the rich — deserved the greatest freedom.

Perhaps the clearest illustration of Hayek’s anti-democratic beliefs was that, while the rightful government and its supporters were actively hunted and murdered in Chile, following a US-backed coup against Salvador Allende, Hayek jetted in to advise the brutal dictator Pinochet on economic policy.

Later, in a letter to The Times, Hayek wrote:

“I have not been able to find a single person even in much maligned Chile who did not agree that personal freedom was much greater under Pinochet than it had been under Allende.”

The freedom he claimed to be so important did not extend to those in prison, exiled, or murdered.

Then, as now, the marginalized and dispossessed do not matter.

Only the rich and powerful matter.

This is the ideological framework that shapes the policies we live by.

Capitalist Extremism.

You don’t matter if you’re not rich.

Over the last few decades, we’ve witnessed the unashamed, overt resurgence of capitalist extremism — or Oligarchy — in almost every part of the world.

Though often wrapped in the flags of violent nationalism, we shouldn’t be fooled. Nationalism is the vehicle, Oligarchy the intention.

The Overton Window (a term used to describe the range of political perspectives considered mainstream — and, by definition, which are considered ‘extremist’) has shifted so far to the right that Fascists, Racists, Colonialists, Oligarchs, and Criminals dominate the tables of power.

Progressive centrists, Social-Democrats, or Centre-Left thinkers (who, a couple of generations ago, would have been considered mainstream) are branded as extremists, or absurd, impractical idealists.

We see openly fascistic, racist and murderous politicians and ‘personalities’ made respectable and ‘relatable’, by media organisations owned by the oligarchs they create policies to support.

Conspiracy theorists get over-excited about secret plots to rule the world. White supremacists talk of Jewish Plots. Racists claim ‘migrants’ are trying to ‘replace them’. All manner of fantasy-violent narratives are promoted and shared.

The real situation is plain to see.

There’s a Class War.

It’s been going on for millennia.

It’s being fought, relentlessly and ruthlessly by the rich against the rest of us.

The phrase ‘class war’ evokes grubby, wild-eyed anarchists in back-street squats. They sit in our imaginations hatching implausible plots to blow up the international top-hatted Barons of Global Capital.

This is so wrong.

Class War is waged by the rich, not the poor.

Sometimes it’s a low-level, attritional war.

Sometimes it’s brutal and leaves many dead.

It’s class war when the poor are left to die on hospital waiting lists, while while members of the ruling class can access private care within a week.

It’s class war when corporations are given tax breaks to ‘encourage employment’, then pay employees so little they need state or charity benefits to survive.

It’s class war when the interests of shareholders are more important that those of employees, wider-society or the natural environment we share.

It’s class war when the army, police and courts deny the right of citizens to protest and disrupt.

It’s class war when communities are told the ties that bind them mean nothing, that individuals should ‘get on their bikes’ to find work elsewhere.

It’s class war when schools no longer offer theatre, dance, music, nor provide the spaces to teach them in, while the private schools the elites send their children to have all these things, and more.

It’s class war when students emerge from education overburdened with debt: debt which the children of the wealthy pay off without a second thought.

It’s class war when young families cannot afford a home — even to rent — while wealthy oligarchs keep buildings empty as ‘investments’.

It’s class war when kids grow up without a proper education, or in homes with mouldy walls, cracked windows and pervasive damp.

It’s class war when the air we breathe, the water we drink, the rivers we swim in, make us sick because corporations have polluted them, while the ruling class jet off to healthier, cleaner, safer places: private islands and exclusive resorts.

It’s class war when ruling class lives are valuable, and the lives of those they rule are insignificant.

It’s class war when the people who make laws don’t intend to live by them.

It’s nothing new.

It was class war when the ruling class broke strikes by workers seeking a living wage and safe conditions.

It was class war when landowners cleared small farmers off their land because sheep brought in more money.

It was class war when working class soldiers were sent to fight colonial wars in foreign lands — expected to die in defence of interests that would never benefit them.

It was class war when the English Ruling Class let the Irish starve, let the West Bengalis starve, let their own home-grown workers starve — or forced the poor to rely on the workhouse or the charity of food-banks.

Sometimes the class war is mixed with racism.

Sometimes it’s mixed with a dribbling, rabid nationalism (though we know the loyalty of the rich in one country is always to the rich of other countries, not to the poor they share a flag with).

Sometimes it’s mixed with some other toxic prejudice.

Sometimes class war is waged with guns and bombs.

Sometimes it’s waged through business.

Sometimes it’s waged in silent neglect, as the poor die on waiting lists and the rich refuse to join the queue.

It’s fundamentally the same war.

The powerful retain power by active or passive assault on those — the majority — they dominate.

They force us to live in ways they’d never tolerate for themselves.

Perhaps you think this is all so much bedsit-anarchist ranting?

What do you call it when the poor must suffer and die, so the rich can remain comfortably in control of every aspect of our lives?

I call it Class War.

Some call it: “the natural order’ or ‘the law of the jungle’.

It’s neither.

The law of the jungle is not limitless competition. The natural order is not dog-eat-dog.

Dogs collaborate. Within their collaboration, they compete.

Living systems evolve through competition within a framework of inter-dependence.

Neither one nor the other. A balance.

A libertarian might argue: ‘Individual freedom is the highest good!’

None of us are purely individuals. We’re connected. We rely on others and — unless we’re psychopaths or narcissists — we consciously serve others too.

To claim unfettered individual freedom is to demand the right no longer to be human.

To be human is to connect.

In a world where money and connections buy power, libertarianism justifies those with most having access to most, while those with least have access to the least.

It’s a complacent, self-centred assertion of the status quo

Some will dismiss my argument saying: ‘Capitalism is the best system there is’.

The ‘only’ other system, ‘socialism’, failed, they’ll claim!

I’ve two responses.

First, we don’t live under capitalism. The world has reverted to oligarchy. Capitalism relies on balance between supply and demand within the market. When a market becomes distorted or is manipulated, balance is destroyed.

Excess wealth buys excess influence, and so destroys balance. Capitalism mutates into oligarchy when excess wealth is acquired or passed from one generation to the next.

Imagine a food market — many small stalls at which individual farmers sell their crops. From week to week prices fluctuate according to what’s available and what customers are willing and can afford to pay. One day an oligarch says he’ll buy everything for ten times the normal asking price. He can afford it. Money’s not scarce for him. The other customers must go home with nothing and will starve (or more likely, have to sell themselves to the oligarch to survive). The sellers cannot negotiate the price because if they try, the Oligarch simply refuses to buy their goods. He’s indifferent. He has more than he needs anyway.

Dynamic balance — the balance at the heart of capitalism — is destroyed.

All power rests with the oligarch.

My second response to the assertion of the supremacy of capitalism is this:

The idea humans are only capable of designing two socio-economic systems is an insult to our ingenuity, and is demonstrably untrue.

There’ve been many different systems over the centuries.

Many more are possible.

Each have advantages and disadvantages.

More specifically, any system advantages some sections of society at the expense of others.

Imagining and creating new systems is possible. The chance to do so is (increasingly) curtailed though. The ruling class are terrified we might create better answers than the ones we currently live by.

What might new systems look like?

Who knows? Thinkers, artists, outsiders, experts, communities, all of us must imagine.

We must put aside fear and adopt humility.

Any new system will entail gains and losses. Some things will be better and some worse. That’s how it is.

There is no ‘perfect’ answer to most questions. When a politician claims they’re ‘doing the right thing’ or implementing ‘the right policy’, they’re engaging in PR, not honest communication.

Every choice advantages some at the expense of others.

If we reject change because we fear something might be lost, we accept stagnation.

That, of course, is what the ruling class want. They want things to stay as they are, because how things are serves them well.

So the rest of us must dare to imagine.

Despite everything I’ve written, my own imaginings don’t involve a blanket rejection of capitalism.

Capitalism is an effective system in some ways. It’s great for guiding small businesses to know what people want — and to be able to charge a fair price. Working properly, it contains core, invaluable guarantees of personal freedom.

The food market I mentioned above works well, until the Oligarch turns up.

Capitalism is flawed, but can be effective.

My opposition is to Capitalist Extremism, to Oligarchy.

Here’s three ideas that could contribute to evolving our societies into ones where everyone matters, not only the rich.

The first is to severely limit the amount of wealth that can be passed from one generation to the next.

As soon as there’s inherited wealth, inequalities of opportunity and power become entrenched. Some people, from birth, matter more than others.

An inheritance-based system formalises privilege.

An argument often advanced with ill-concealed fury, is that restricting inheritance will discourage people from working hard to advantage their children.

This is nonsense. While passing security to the next generation is one element of what motivates people, it’s not the only motivation. If you’re living in a society where basic needs are properly attended to, the fearful need to protect your children against destitution would decrease.

Anyway, have the rich who pass on their wealth and networks of influence really ‘worked hard’ ?

Some of them have.

Plenty have not.

Do we really believe it’s morally good for someone today to enjoy massive advantages because their ancestor trafficked in slaves? Or ruthlessly exploited child workers in the nineteenth century?

Do we want to insist on the right of people to have a disproportionate say in the future of the nation, because their ancestors threw peasants off their land to raise sheep instead?

Is it morally laudable to live on wealth stolen from countries and peoples brutalised and despoiled through colonialism?

As a quote attributed to Balzac puts it:

“Behind every great fortune is an equally great crime.”

Sometimes it’s not even as exciting as a ‘great crime’.

One of the UK’s wealthiest people is The Duke of Westminster. When he inherited his title and fortune from his father, he AVOIDED inheritance tax of nearly 4 Billion Pounds through the entirely legal, wealthy-advantaging structure of trust funds.

Did his ancestors work hard to create the wealth they passed on to future generations?

No.

As The Guardian explained in an article in 2023

The Duke of Westminster is accidentally obscenely rich and that accident buys him a place at the heart of the British Establishment.

I’m not suggesting since then his family has not worked. No doubt they’ve worked assiduously to preserve and increase their wealth and power. They’ve worked for themselves only, not for the benefit of everyone else.

The structures they’ve put in place to protect their fortune — the trust funds and opaque corporate organisation — work AGAINST the rest of us, depriving us of taxes that might pay for a functioning health service.

Strictly limiting the amount of inheritance that passes down the generations would increase the possibility for all citizens to participate in society, if, and only if, it’s accompanied by some kind of universal basic income.

This is the second transformative idea.

Immediately I hear screams of protest.

Universal Basic Income (UBI)! It’s the work of the devil!!!!!!

One argument against a UBI — the most common one — is that it’s ’giving money to people for doing nothing’.

This is considered a moral outrage.

Money for nothing?

Inherited wealth is ‘money for nothing’.

Did Trump Jr. earn the money he inherited? Did the children of oil-rich oligarchs, cosseted celebrities, or your local Eton-educated aristocrat, work for the advantages they have?

Of course they didn’t.

The ‘money-for-nothing’ argument, implying UBI is immoral, is a fiction created by privileged people who don’t want others to have the advantages they themselves possess.

As bell hooks writes in her book ‘All About Love’:

‘One of the ironies of the culture of greed is that the people who profit the most from earnings they have not worked to attain, are the most eager to insist that the poor and working classes can only value material processes attained through hard work. Of course, they are merely establishing a belief system that protects their class interests and lessens their accountability to those who are without privilege.” (p.150)

In key ways a UBI would reinforce genuine capitalism, not undermine it.

If individuals didn’t live in fear of utter destitution, the laws of supply and demand — at least as they apply in the labour market and at the level of individual consumer choice — would actually work better.

If people did not HAVE to take a job in order to survive, they could make genuine choices. Potential employers would have to offer wages and/or working conditions to attract potential recruits. Supply and demand would operate significantly more effectively if potential employees were not driven by desperation.

Probably CEOs would get paid less.

Probably bankers would get paid less.

Probably (unfortunately) Artists would get paid less (though we’d at least be able to survive and pursue our art, which would be a step forward from the current situation).

Refuse collectors would probably get paid more.

So would care workers.

We’d have to pay a worker what their job is actually worth.

There’s the problem. That’s why the notion of limiting inheritance and introducing a UBI provoke such howls of outrage.

A UBI offers choice, empowerment and dignity to those who currently have little or none. It expands the distribution of participation and power.

It wouldn’t stop the current elite from full participation in society, but would reduce their disproportionate ability to have everything organised to advantage only them.

The third transformative idea? Remove the right for the wealthy to opt out of the systems the rest of us rely on.

Nothing would improve the heath system faster than if the powerful knew they had to rely on it.

Nothing would ensure the proper funding of schools faster than the rich knowing their kids will be educated there.

People will scream ‘communist’ or ‘socialist’.

I don’t mind — those words aren’t insults.

They’re simply inaccurate.

I’m not talking about socialism or communism.

I’m talking about collective responsibility.

Citizenship.

Mutuality.

Interconnection.

Informed and empowered, genuine democracy.

The real law of the jungle — competition within a web of interconnected collaboration.

The myth we’re sold, of the primacy of the individual, is exactly that — a toxic myth touted by the few to control the many.

As bell hooks writes:

The rugged individual who relies on no one else is a figure who can only exist in a culture of domination where a privileged few use more of the world’s resources than the many who must daily do without. Worship of individualism has in part led us to the unhealthy culture of narcissism that is so all pervasive in our society. (‘All About Love’: p. 245)

Change won’t happen easily, nor with the consent of the ruling class.

They’re fighting a Class War.

Meanwhile.

My heart beats, as it has for nearly 60 years now.

I listen.

I’m grateful for each beat, and hope there’ll be another one. There’s damage in there, but I don’t know if it’s bad and worsening, or nothing much to worry about.

In bad moments I see death sitting by my side.

If I were rich, would I buy myself a better chance of survival?

I don’t know.

I’m not rich.

My parents came from working class backgrounds and the savings they accumulated paid for the care my mother needed in the last years of her life.

The rich put their money in trust funds or tax havens.

The rest of us pay our own way.

I inherited very little. It took the financial pressure off for a month or two after my first heart attack and I was glad of it. But it made no substantive difference to me.

So I don’t know what I’d do if I were actually rich.

I know such choices should not be left to fearful individuals with unequal capacity to buy survival.

Access to proper health, education, culture, natural environment and the many other elements of a rich life, should be systemic questions, not individual ones.

We’ll each inevitably choose what we can afford, when faced with life-changing or life-ending moments. If we think all citizens have equal value, none of us should see our very capacity to survive diminished by relative poverty.

Do we want to give greater freedom, worth and value to some than to others?

Are some of us more equal than others?.

No one should die waiting for treatment — especially when those who make policy don’t live by those policies, and have more choice than the rest of us.

Society — to the limits of what it can afford — should run systems and enact policies that serve all citizens, not only the elite.

When I read back on what I’ve written, it says many things I believe to be true.

Perhaps you disagree.

That’s fine.

Thinking and writing is part of how I make sense of the world.

It’s also my distraction.

You see, I’m scared.

I’m on a waiting list and I may die before my turn comes to be given a diagnosis and relatively simple treatment.

My life.

My only life.

Scared.

And angry.

Because it doesn’t need to be this way.

Angry also because though — like almost all of us — I matter to me, I seem not to matter to the society I’m part of.

I don’t matter because I’m not rich.

After thirty years performing, directing and teaching around the world, now I coach and mentor artists and others to live in joy and creativity. I also still perform sometimes, but usually keep my clothes on.

I recently published a free training ‘How to make BIG decisions when you feel really stuck’. It’s a PDF and video. You can get your copy here.

More information about me here: www.johnbritton.co

Email: [email protected]